Vestibular neuritis

Vestibular neuritis is a common cause of peripheral vertigo. It is a good example of the sudden unilateral suppression of vestibular information involved in the maintenance of balance and the steadying of the gaze.

Vestibular neuritis symptoms

Vestibular neuritis results in the sudden onset of rotational vertigo with nausea and vomiting. It is essential to note that when the patient is questioned, no auditory problems are detected (deafness, tinnitus). Given the intensity of the vertigo, it is not uncommon to find these patients in A&E units.

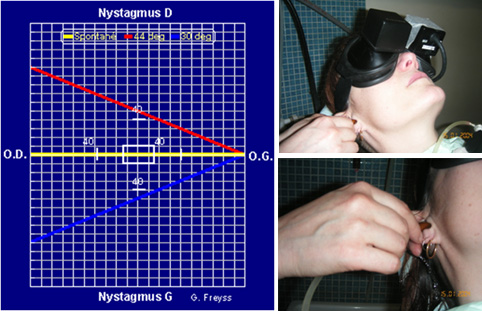

The videonystagmoscopy examination identifies a spontaneous peripheral nystagmus, which is horizontal and rotational, unidirectional, and less substantial and less frequent during ocular fixation. The rapid phase of this nystagmus is directed toward the healthy ear. The other aspects of the examination, in particular the neurological examination, are normal. As time goes on there is a regression in vestibular symptoms. In a few days, the rotational sensation and neurovegetative manifestations will improve. The sensation of imbalance will remain for some time.

Other tests

The caloric and rotational tests confirm areflexia of the horizontal canal nerveand eliminate a central cause. The patient does not respond to hot or cold stimulation on the affected side nor to rotating the head horizontally towards the damaged side. Only a destructive nystagmus is recorded. These tests demonstrate the horizontal canal nerve dysfunction.

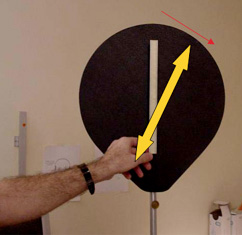

The head impulse test shows the deficit in horizontal vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Myogenic evoked potentials induced by sound stimuli show normal reflexes in the saccule and the sacculospinal pathways in 2/3 of cases. This demonstrates that normal sensitivity is preserved in the saccular nerve and therefore the inferior vestibular nerve.

These forms, sparing the saccular vestibular nerve and probably the inferior vestibular nerve (which is composed of the saccular nerve and posterior canal nerve), have a good prognosis and they often evolve toward recovery of normal vestibular nerve sensitivity in less than a year. However, in one third of cases, the saccular responses are eliminated, which indicates more diffuse damage of the vestibular nerve.

The subjective vertical perception test shows most often a misperception of the vertical plane, tilted to the side of the lesion by more than 10°.

These tests are essential because they confirm the cause of the vertigo induced by a sudden malfunctioning of the vestibular nerve from the inner ear. The audiogram and impedance measurements must always be carried out. They confirm the absence of cochlear impairment.

A brain MRI is only required when there is an atypical combination of neurological signs or headaches. It will eliminate a central impairment and also an acoustic neuroma, which must always be considered, although it is seldom revealed by significant rotational vertigo.

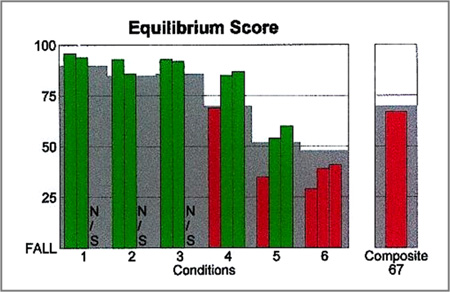

The EquiTest initially shows a very low score under conditions 5 and 6 (see figure below), platform controlled, eyes closed (5) or stabilized vision (6), conditions that test the involvement of the vestibular system in balance functions. The score will then improve over time. Vestibular rehabilitation with a specialist physiotherapist may be useful in helping the patient to regain normal balancing functions. Lastly, in the forms of neuritis sparing the inferior vestibular nerve, it is not uncommon to observe subsequent positional vertigo.

Causes

The cause of the condition appears to be viral.

There are three arguments for this:

• The epidemiological context with the notion of occurrence in seasonal or family epidemics, an infection of the upper airways in the weeks before the incident, the existence of a concomitant cranial polyneuropathy.

• Serological tests that show a protein concentration suggestive of demyelination or antiviral antibodies. The virus responsible cannot be identified. However, the herpes simplex virus seems the most likely candidate.

• Histopathological studies of the pyramids that have found characteristic viral lesions. Following inaugural infection, the virus spreads in the body and remains dormant in the ganglia of certain cranial nerves including the vestibular ganglia. When the patient has an intercurrent condition, the virus is woken and induces an autoimmune reaction responsible for inflammation, oedema and demyelination.

In some cases the cause may be vascular, particularly in hypertensive patients or those prone to vascular problems.

Treating vestibular neuritis

The first goal is to relieve patients of vomiting and severe dizziness. The patient is isolated and prescribed major vertigo medication, antiemetics, and even sedatives. The latter should only be prescribed during the critical period as, beyond this, they would delay central vestibular compensation. High but rapidly regressive doses of systemic corticosteroids can also be recommended, as well as antivirals. Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of corticosteroids, which corresponds to the pathogenesis of vestibular neuritis as a viral oedematous neuropathy.

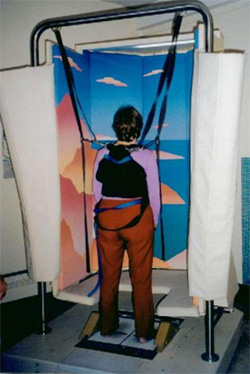

Once the acute phase has passed, the treatment is based on energetic movements. The patient stands as quickly as possible to facilitate central vestibular compensation. Gradually, other afferent activity from deafferented vestibular nuclei, visual, proprioceptive and contralateral vestibular afferent activity, will replace the afferent vestibular activity missing. Vestibular rehabilitation practised by specialized therapists facilitates this compensation and therefore the recovery of normal oculomotor and postural stabilization reflexes.

CONCLUSION

Vestibular neuritis is often illustrated by a disastrous picture associating great rotatory vertigo with nausea and vomiting.

The otoneurological workup is essential since it confirms the vestibular nerve lesion originating from the inner ear and makes it possible to specify the spread of the lesion to the upper and lower vestibular nerve.

The prognosis is generally good, but patients should be monitored until recovery.

A brain MRI scan, focusing on the internal ear canals, may be needed to rule out a central cause such as a stroke.

Immediate treatment is based around corticosteroid therapy and antivirals. Following this, a well-conducted vestibular rehabilitation programme promotes a return to normal balance for the patient and the disappearance of their feelings of instability.